Few discoveries can truly take one back in time, but stumbling upon a 66-million-year-old sample of dinosaur vomit certainly makes the cut. Unearthed in Denmark, this extraordinary find offers a visceral glimpse into the prehistoric world, revealing not only the dietary habits of ancient reptiles but also the intricate details of an ecosystem that thrived in the twilight of the dinosaur age.

The fossil, identified as regurgitated remains, has brought paleontologists closer to understanding the feeding behavior of some of Earth’s most dominant creatures. Encased in a chalky limestone deposit, the material stands as a vivid reminder of life during the late Cretaceous period. Its composition—a mix of partially digested bones and other remnants—tells a story far more complex than a standard fossilized skeleton ever could.

The site of the discovery, located in the Danish region of Stevns Klint, is a UNESCO World Heritage location. This area is already renowned for its insights into the catastrophic asteroid impact that marked the end of the dinosaurs. However, this particular find shifts focus to a more specific—and, frankly, unexpected—aspect of the prehistoric world: the act of regurgitation itself.

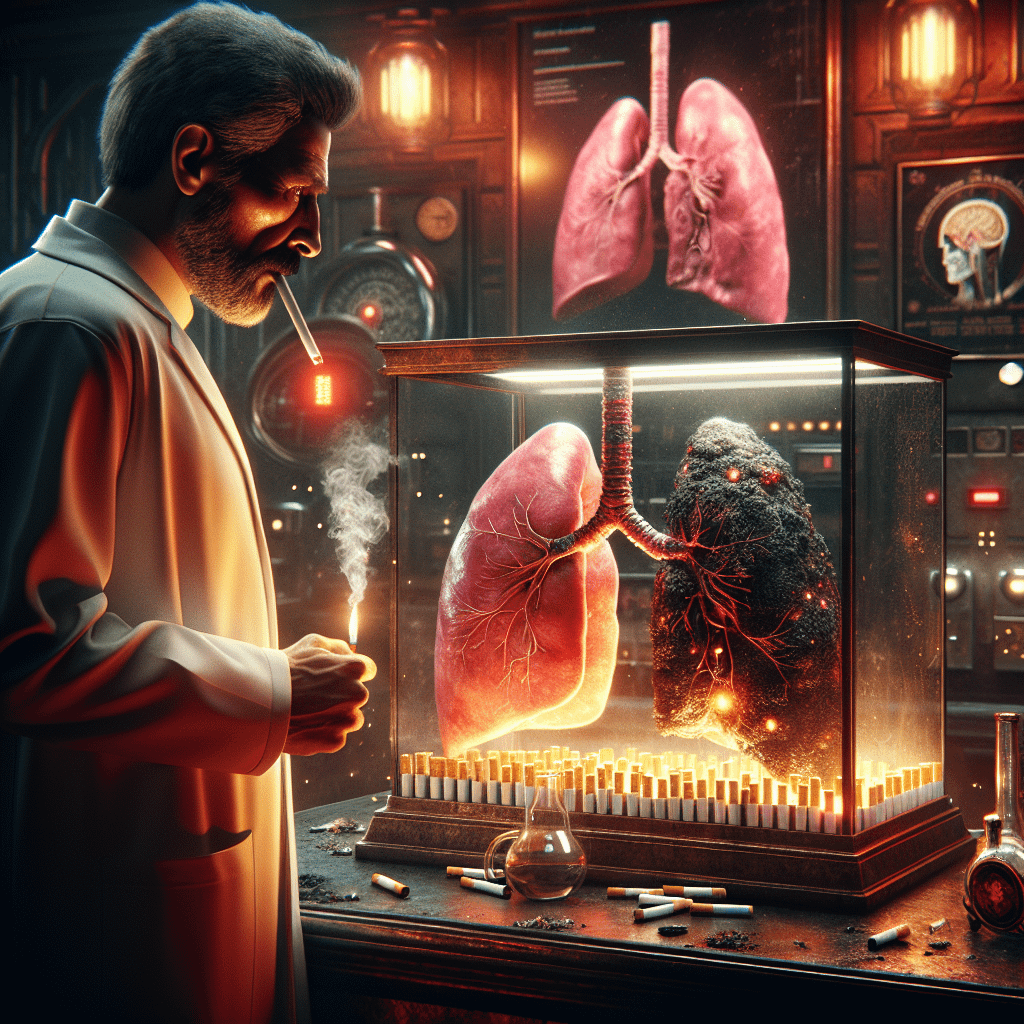

The vomit in question likely belonged to a large predatory dinosaur or an ancient marine reptile. While the exact species remains unidentified, the partially digested remains suggest the creature’s meal consisted of smaller prey, possibly fish or other marine animals. The acidic environment of the predator’s stomach would have softened the bones before they were expelled, creating the unique fossilized material unearthed today.

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond the novelty of finding fossilized vomit. It provides a rare opportunity to study predator-prey interactions during the Cretaceous, offering insights into the food chain dynamics that governed these ancient ecosystems. Unlike fossilized feces, or coprolites, which have been studied more extensively, regurgitated material offers a snapshot of what creatures were eating without the additional complexities of full digestion.

The preservation of this material is remarkable. The chalky limestone of the Stevns Klint region acted as a natural time capsule, shielding the fossil from the elements for millions of years. This level of preservation is unusual for such fragile organic matter, making this find even more significant.

Research into the vomit’s composition has revealed patterns that suggest it was expelled in a single event, possibly during or shortly after the predator’s meal. Such behavior is not uncommon among modern carnivores, which sometimes regurgitate indigestible material to avoid complications. This discovery provides a direct link between ancient predators and their modern descendants, highlighting behavioral consistencies that have persisted over millions of years.

The scientific team behind the find is now working to analyze the fossil in greater detail, utilizing advanced imaging techniques and chemical analysis to identify the specific prey species and gain further insights into the predator responsible for the regurgitation. These methods could also help determine the environmental conditions of the region during the late Cretaceous, painting a more complete picture of life at the time.

Beyond its scientific value, this discovery serves as a reminder of the complexity and interconnectedness of ancient ecosystems. Each fossil, no matter how unusual, adds a piece to the puzzle of Earth’s history, revealing how creatures lived, interacted, and ultimately adapted to their surroundings—or failed to do so.

While the dramatic extinction event that followed this period wiped out the dinosaurs, their legacy remains etched in the fossil record. Finds like this regurgitated material offer a rare, unfiltered glimpse into their daily lives, bridging the gap between an ancient world and the present day.